For Tomás Navarro Tomás and his team, phonetic transcription was of capital importance when it came to gathering and publishing linguistic data. This was normal in European philology at the time. Ramón Menéndez Pidal had sent Navarro Tomás with a scholarship from the Junta para la Ampliación de Estudios to study in the best phonetics laboratories in France, Switzerland and Germany. On his return to Madrid Navarro Tomás created the Phonetics Laboratory as part of the Philological Section of the Centro de Estudios Históricos, and in fact the ALPI was framed as part of the work of the Laboratory.

On the importance of phonetic transcription in the Atlas, Navarro Tomás wrote:

El valor demostrativo de estos mapas […] es mérito de la detallada precisión de sus transcripciones. Una investigación realizada con menos rigor analítico y con transcripción menos estrecha, habría resbalado por encima de muchos de estos pormenores tan significativos para el cabal conocimiento de la materia. En efecto, no se trata de detalles fuera del alcance de una observación adecuada. Son sentidos de manera general, pero sólo adquiere conciencia de ellos el oído adiestrado para definirlos.

Visto a la distancia de los cuarenta años transcurridos, no se puede decir que el plan del ALPI ni el método seguido en su elaboración hayan perdido actualidad ni consistencia. Si hoy hubiera que repetir la empresa, habría que aplicar las mismas normas. No se ha descubierto manera de estudiar la lengua popular sin ir a buscarla a su propio terreno. Tampoco hay modo de representar esa lengua sin imponerse limitaciones de sujetos y de lugares. Los aparatos mecánicos sólo prestan una ayuda relativa. El oído convenientemente ejercitado sigue siendo el instrumento más perfecto. Muchas veces, al repasar en la oficina una cinta magnetofónica, se echa de menos la presencia de la persona que la inscribió.

[The documentary value of these maps […] is a virtue of the detailed precision of their transcriptions. Research conducted with less analytical rigour and with a less narrow transcription would have glossed over details which are so significant for a full understanding of the subject. Indeed, it is not a matter of details which are out of the range of proper observation. They are generally heard, but only an ear which has been trained to distinguish them becomes aware of them.

Viewed after the passage of forty years’ time, neither the plan for the ALPI nor its methodology can be said to be any less current or coherent today. If one had to repeat the experiment today, one would have to apply the same standards. No method has been discovered for studying the language of common people without going to look for it where they live. Nor is there any way to represent that language without imposing limits on topics and localities. Mechanical devices only help to a certain degree. The properly trained human ear is still the best instrument. Oftentimes, when reviewing a tape-recording in the office, one wishes the person who collected it were present.]

(Navarro Tomás 1975: 19)

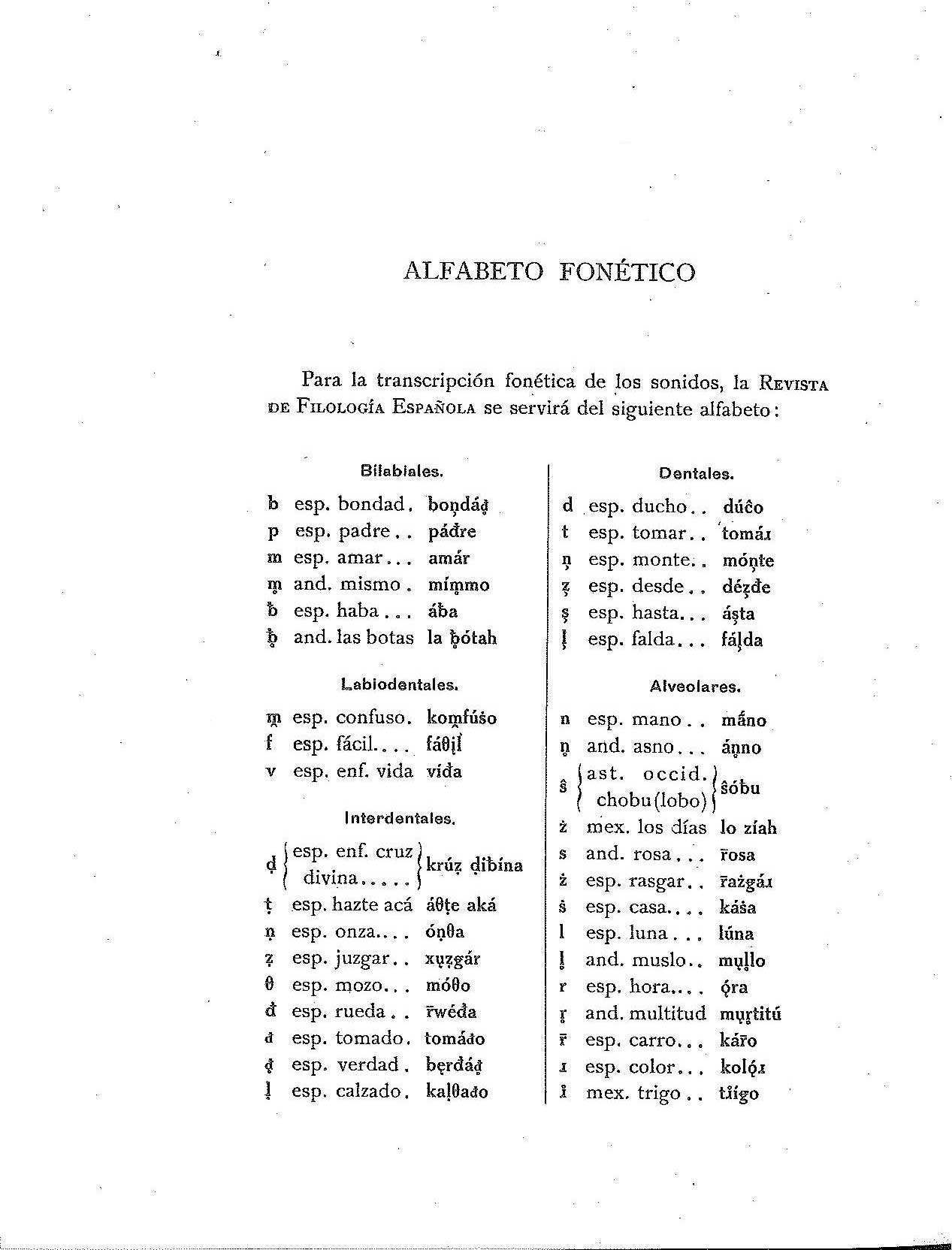

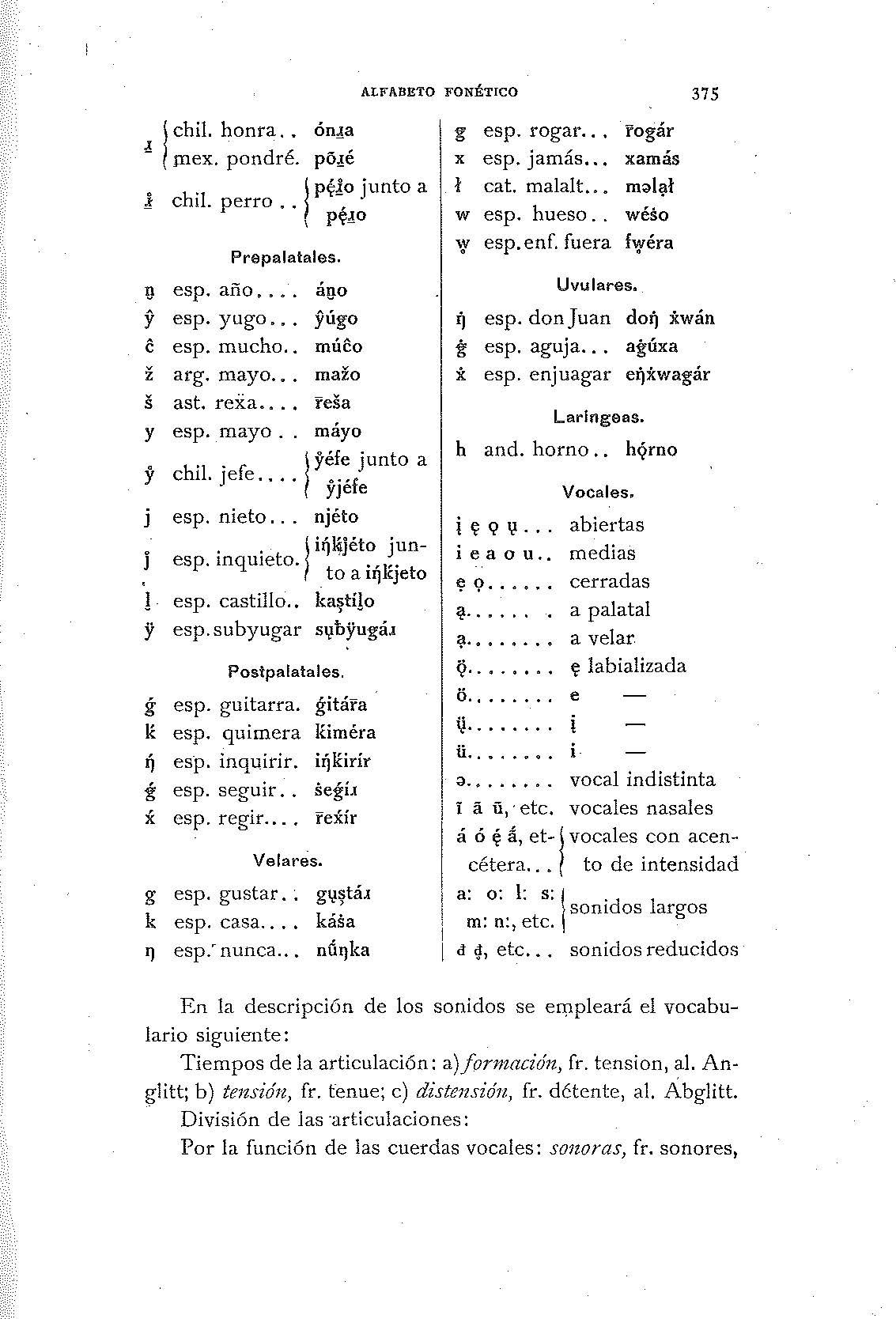

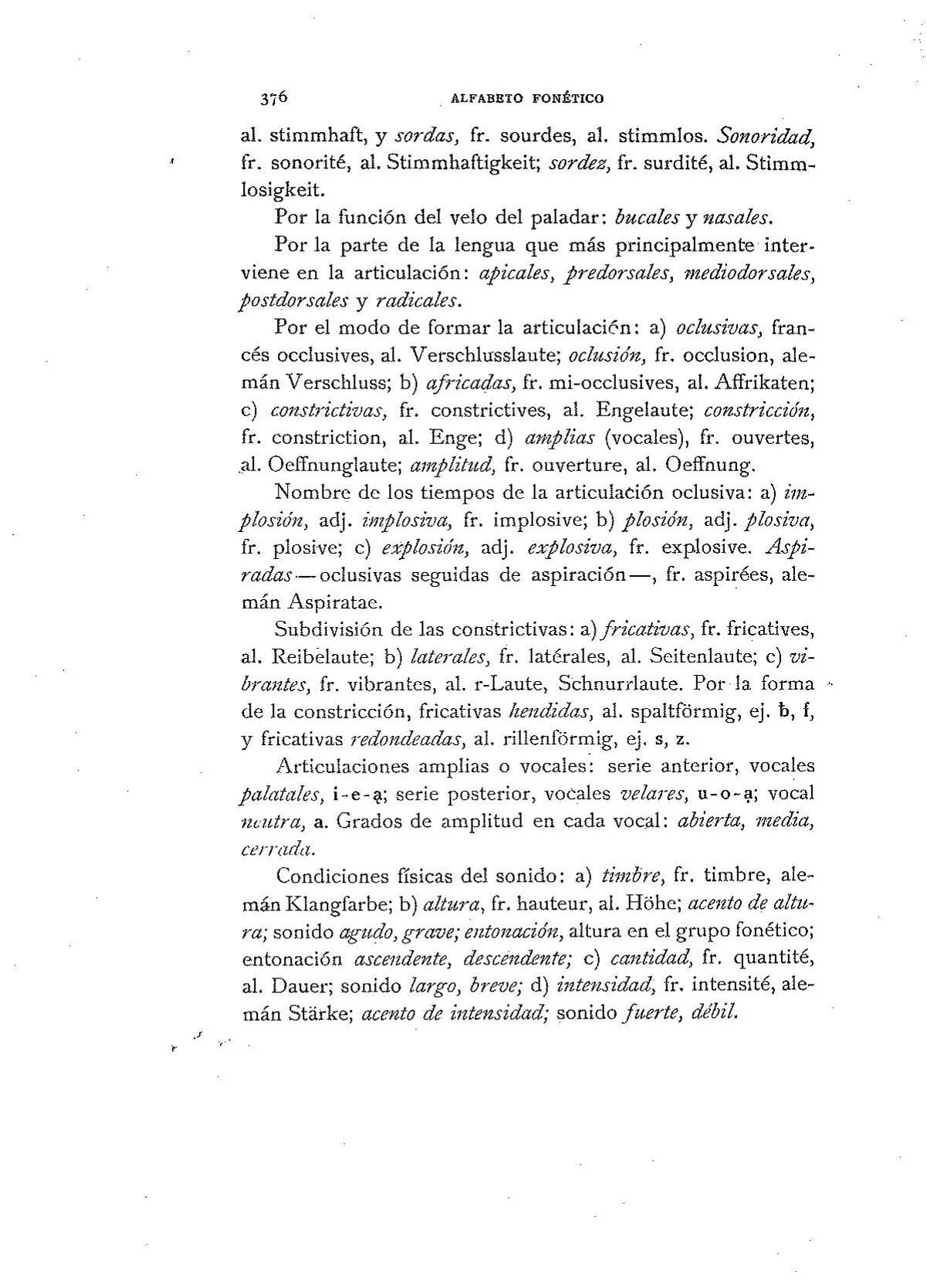

The creation of the Revista de Filología Española phonetic alphabet or ARFE (RFE, II, 1915: 374-376) is something we owe to Navarro Tomás. Extraordinarily rich in nuances, it is an alphabet that adapts the transcription system used in other European atlases to Iberian speech varieties and incorporates some symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Navarro Tomás himself took charge of training the future atlas fieldworkers in the rigorous use of this alphabet which for some time has been a reference point for most of the linguistic atlases in the Hispanic world.

The phonetic alphabet in the Revista de Filología Española

The Introduction to the ALPI dedicates eight large-format pages to a detailed description of the alphabet used, including an explanation of why they chose to simplify the fieldwork transcriptions when it came to mapping the data:

Se estimó conveniente simplificar en algunos casos las transcripciones fonéticas sacrificando ciertos matices, con el doble fin de unificar el criterio de los transcriptores y de facilitar la lectura de las notaciones; en esta labor se tuvieron muy en cuenta las instrucciones de don Tomás Navarro.

[It was deemed appropriate to simplify transcriptions in some cases, sacrificing certain nuances, with the double objective of making transcribers judgements more uniform and making the data easier to read. In this process Navarro Tomás’ instructions were followed very closely (/kept very much in mind)]

(Introducción al ALPI, 1962 : 6)